24 Jun In business contracts, plain English is better than legalese

You know that feeling when you read a legal document and you think Why isn’t this written in plain English? Why is everything “whereas” and “hereinafter?” Can’t they write it in a way that people can understand?

Yes. You can have contracts that people can understand. And if you’re a business, why shouldn’t you write your contracts this way? After all, how does a contract help you if you or your customers don’t understand what it means? Well, good news: your legal documents can be in plain English. They can be informal, even funny. In fact, sometimes this type of legal writing can further both your business goals as well as your legal goals. For companies with a young, casual, hip, or playful image (or customer base), this style can reinforce your brand.

Our firm works with innovators and outside-the-box entrepreneurs who seem to challenge historically accepted concepts. One piece of conventional wisdom that we enjoy disrupting with them is the notion that legal documents need to have convoluted language. And we love a challenge! When we ask our clients “how can we help?” they often say: “I just want a short, simple contract. One that protects me and my business’ interests, but doesn’t have all that legalese that no one can understand.” So our goal is to strip the fat and make it readable while protecting clients’ interests.

This isn’t a new idea. Major companies around the world are re-writing their contracts so customers and partners can read them. Here are some that we love:

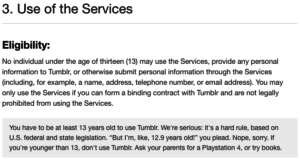

Tumblr

Blogging site Tumblr is doing pretty well: it hosts 266 million blogs, has 13 billion views to date, and has $125 million in outside investment. Their lawyers did an awesome job crafting the Tumblr Terms of Use in a user-friendly manner. For example, when it came to the clause that tells users they must be at least 13 years old (important to protect the website from liability for underage users), they wrote this:

That’s funny. But it’s also a 100% legally binding contract that accomplishes the company’s goal of protecting itself. And it does it in a way that matches the company’s young, hip, accessible branding. Perfect.

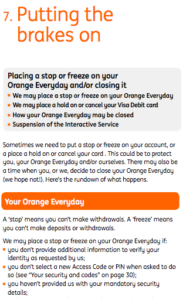

ING Direct

ING Direct, the multinational bank, needed to explain to its customers that it might freeze their accounts from time to time. Its lawyers wrote something that anybody can understand:

Again, this is clear, understandable, and a little informal. “Putting the brakes on” is much better than “Measures that Company may take in its sole discretion to cease specified account activities with immediate effect.”

In Practice:

It may sound wicked nerdy (ok, it is wicked nerdy), but we’ve actually been having fun turning accepted legal “form” contracts into readable (and binding!) documents for the many (not the few). And while for some deals it doesn’t make a lot of sense to give a document this treatment – because the people reading them are primarily lawyers anyway – the ones that do tend to matter most are those that are most commonly read by good, normal people (read: non-lawyers; we strongly dislike the term “laypeople”), such as Service Agreements, Independent Contractor Agreements, Employment Contracts, Website Terms of Use and Privacy Policies, and Residential Leases. Remember, while it’s generally advised that you have a lawyer review all of your contracts, you really shouldn’t need a lawyer to review some of the simple ones.

At the end of the day

Your goal, when you use a contract, is to make sure you and the other party understand what it means, and what you’re agreeing to. There is no inherent problem with an agreement written in plain English, and in a casual, hip, or funny voice (as long as it still protects you legally), and it may even be better for your business goals. If you strongly agree, don’t settle when working with your lawyer to craft something that works for your business.